I read Charlie Francis' book the Speed Trap, so you don't have to.

Here are 5 key lessons from one of the best sprint coaches ever that can help you better understand the art of training speed (without the doping).

While these 5 lessons don't entirely summarise or capture the depth of Francis' training philosophy, I chose them based on how relevant they were to my personal experience doing this sport for 7 years now.

I had to learn some of these lessons the hard way. Hoping some younger sprinters will get value out of this, because a younger version of me for sure would have.

1. Less is More

Francis learned that training volume should be minimised while maintaining high intensity.

Overloading athletes with excessive training leads to fatigue, sub-optimal performance and in the worst case, burnout.

This is why 'work smarter, not harder' carries a lot of merit, especially in sprint training.

Francis believes that short intense high-quality efforts with adequate recovery are more effective for training speed.

However, it's important not to view this as binary. I've personally been at both ends of the spectrum, doing too little volume and doing too much volume.

There's a time and place for low volume & high intensity (SPP), and for high volume & low intensity (GPP).

What matters most for speed, assuming you have a good base of strength, aerobic and anaerobic fitness, is high quality short intense sprints paired with adequate recovery.

How can you implement this in your speed training?

A good rule of thumb is to take 1 minute of recovery for every 10 meters covered with high intensity effort.

For a 60 meter training repetition above 90% effort, 6 minutes recovery is a good starting point. Adjust through experimentation and what works best for you.

The faster I've gotten, the more recovery I've needed for these types of sessions.

A flat-out 60m in a session targeting speed & quality would require at least 10 minutes of recovery for me.

2. Central Nervous System Recovery

Francis talks about how high intensity training places significant strain on the central nervous system (CNS).

Types of training that can induce significant strain on the CNS include:

→ Heavy weightlifting

→ Speed work

It takes approximately 48 hours for the CNS to fully recover from these types of sessions.

Scheduling your high intensity training days in a way that allows your CNS to recover fully will ensure you get maximal benefits and avoid overtraining.

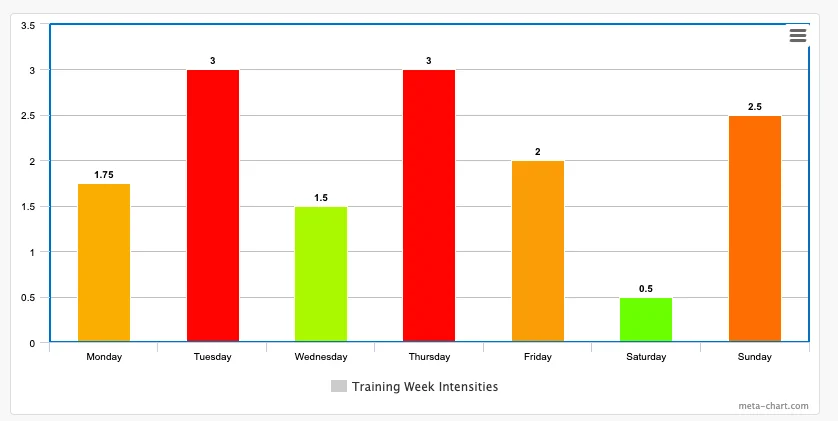

This is how my current training week looks in terms of session intensity, I train 6 days per week.

→ Monday & Fridays I lift.

→ Tuesdays & Thursdays are my acceleration and speed days.

→ Wednesdays is for tempo recovery runs.

→ Saturdays is my rest day, I usually go for an hour long walk.

→ Sunday is my speed endurance day, usually do sleds or hills on this day.

3. Massages & Injury Prevention

Francis was a big believer in massages for injury prevention and recovery. It was a key tool in his programs.

I also believe strongly in regular massages and attribute my most successful & injury free seasons to this habit.

Tight muscles need to be loosened regularly, whether it be self massaging or by a trained professional.

I personally self massage every day, using tools like hockey balls, hard foam rollers, barbells and my hands to target & release muscle tightness.

Resolving muscle tightness increases range of motion & blood flow to the area, ultimately speeding up recovery.

I haven’t been to a physio in over 3+ years and believe I’ve remained injury free mostly because of this daily habit.

It’s your body and you have it for life — learn about it and take agency over its maintenance.

If not addressed regularly, muscle tightness can quickly snowball into movement pattern inefficiencies and bad compensation patterns. These, compounded over time, eventually leads to acute injury.

4. Constant Refinement & Iteration

Francis believed in constantly re-evaluating and adjusting his training plans. He removed any drill that didn’t serve a clear purpose, and focusing in on what provided the best results for his athletes.

As a Bruce Lee once said:

“Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

The ability to adapt quickly to your changing needs as an athlete is far more beneficial than having a stubborn & rigid approach to your training program.

It’s important to test periodically, identify what’s improving, identify the drivers for this improvement and to adjust the program accordingly. Likewise with removing that which is not serving your end goal.

Following a 12-week training program without continually assessing your progress against the end goal is foolish. I understand a lot of sprinters won't or don't have access to high quality testing equipment but it's still important to make do with what you have. Get a cheap stopwatch and record the times you run in training week in and week out, write this down in a training journal.

Do this long enough and you create your own bank of training data. Data patterns will become clear to you and point you in the right direction. If you want to be competitive, you must do this -

"what get's measured, get's managed."

5. Maximal Speed for Sprint Development

Francis advocated strongly for the need for sprinters to train at race pace regularly to engrain the qualities of high-speed movements into muscle memory.

Ever noticed why NCAA collegiate sprinters seem to outperform some of the world’s best every year?

One key factor is the high number of quality races they run in a single season. This constant exposure to high-level competition supports Francis’ philosophy—they become faster simply by racing more frequently against top-tier competitors than sprinters elsewhere.

If you’re not a collegiate sprinter, get into a good sprint training group, and run fast repetitions against sprinters at your level or higher.

Don’t shy away from competition, even in training, if you do, you will be found out when the racing season comes around. Remember, iron sharpens iron.

Final thoughts

Everything mentioned above is helpful as a framework, but only you can find out what's truly best for you, don't be afraid to experiment with your training, whether it's different sprint workouts, drills, recovery periods, recovery methods - every athlete is different, and a coach is there to guide you in the right direction, but ultimately, you're the one steering the ship.

Where that ship lands is directly correlated to your curiosity regarding improvement and your self belief regarding what you can achieve.

If you believe something, it is almost impossible for you to behave in a way that is incongruent, out of alignment or not conducive to the ascent of that belief.

In other words, if you don't believe you can run a certain time, it's almost impossible to do so from the get go. It's better to be delusional and fall short, than to be self limiting and to never fully try. Your behaviours are filtered through the beliefs you carry.